Dreaming the Archive as a Practise of Freedom

A Reading of 'Venus in Two Acts' by Saidiya Hartman

I have spent a lot of time these last couple of months thinking about archives and archival. The noun and verb forms of archive are the same, binding the object and action into a single shape. This shape is both the absolute existence of the archive and, simultaneously, also the creating, adding, subtracting, reproducing, demystifying, and repurposing of all the elements that constitute it. The word ‘archive’ has always felt like a placeholder for something that cannot be hemmed by language. When I think about the archive I think about bodies—personal, public, muscle memory; bodies—knowledge, work, literature; bodies—oceans, deltas, seas; bodies—power, history, narrative. To exist in a body is to be, and by virtue of the shape that this particular grammar lends us, then to exist is also to do. How are we doing? How are we being?

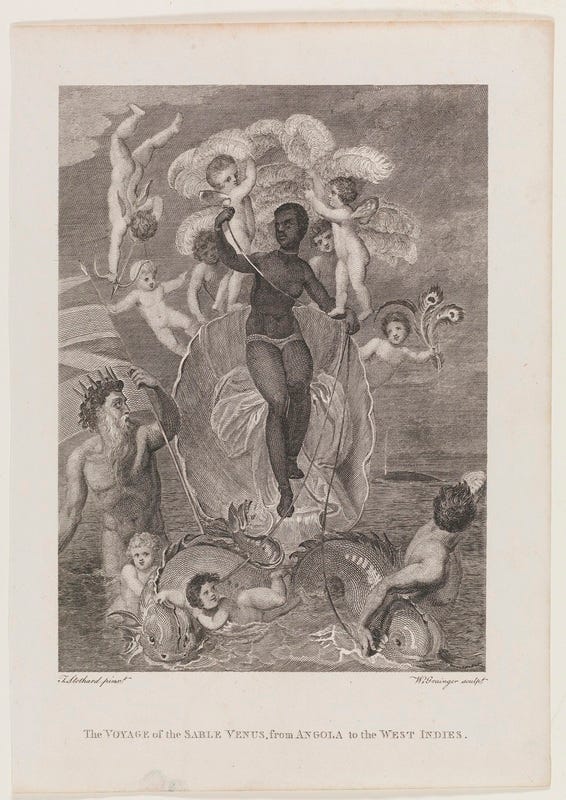

Recently I came across ‘Venus in Two Acts’ by Saidiya Hartman, by way of Machado (In The Dream House) and Olufemi (Experiments in Imagining Otherwise). Hartman traces the figure of Venus as an enslaved woman in the archive of Atlantic slavery—‘undone’ by both imperialism and the resulting “grammar of violence”1 she has been written into. What we know of bodies (personal, public) that are subjugated by other bodies (power) is often elucidated primarily via their encounters with these same bodies (power). Venus, like other enslaved peoples, spends much of her life crossing a body (ocean) against her will, and is then written into a body (history, narrative) that does little to account for the violent structures of imperialism and patriarchy.

The archive is, in this case, a death sentence, a tomb, a display of the violated body, an inventory of property, a medical treatise on gonorrhoea, a few lines about a whore’s life, an asterisk in the grand narrative of history. Given this, “it is doubtless impossible to ever grasp [these lives] again in themselves, as they might have been ‘in a free state.’”2

There are 3 things Hartman addresses that I found particularly interesting.

First: the conflict inherent in use of language/s imposed on us by colonial rule to articulate our oppression.

I gestured to this briefly in my first piece here when I talked about finding comfort in the folds of a language that has only been able to reach me through generations of violence—“our inheritance [is] the brutal Latin phrases spilling onto the pages of his journals” (Hartman, 2008).

Second: interrogating the function of stories.

Hartman first posits this as something that doesn’t afford much: is it “[a] way of living in the world in the aftermath of catastrophe and devastation? A home in the world for the mutilated and violated self? For whom—for us or for them?”, but later suggests that stories could function as “a form of compensation or even as reparations, perhaps the only kind we will ever receive”. If I’m being honest, I have not yet figured out what stories can do or how we should think about them. When I say I believe in the power of storytelling what I mean is, at this moment, there is value to be derived from the perfunctory act of telling. That value could be 1) money by way of mutual aid, 2) a job or scholarship by way of a personal statement, or (more often than not) 3) humanity, because for some reason we need people to turn themselves inside out before we extend this.

When so much of an existence is organised historiographically—slave, migrant, refugee—and the socio-political orders that render these categories of people are built on violence, the stories that arise end up becoming a catalogue of statements, platforms, institutions, and actors that license people’s deaths. Does everyone have a story to tell and can all stories be told? Surely, and impossibly.

Third (and also most compelling to me): emancipating people who have been killed twice—first by state violence, literally, and second by the archive, metaphorically.

Here is where the archive, as a body, adopts its most menacing form. It is not the elegant terrains of a human body, a profound collection of art, or a soft river. Instead it is the straightjacketing of people in their wholeness, in their humanity, to their manner of exit from the world. The point at which Venus leaves the world is also her point of entry into history. Before death at the hands of incredible power, she had no name, no face, no body. No archive.

I chose to call this ‘dreaming’ the archive because I like the fabulation it implies. To “liberate [people] from the obscene descriptions that first introduced them to us” and “exhume the lives buried under this prose” (Hartman, 2008) we need to tell an impossible story while amplifying the impossibility of its telling. This requires imagining that which hasn’t been told, that which cannot be verified; placing ‘fiction’ firmly within the spectre that we call history and slowly releasing the chokehold that imperial bodies (power) have had on other bodies (personal, public, knowledge, literature, history) for so long. Hartman coined the term ‘critical fabulation’3, which uses speculative narration as a means of redressing history. It is beautiful and freeing.

“By playing with and rearranging the basic elements of the story, by re-presenting the sequence of events in divergent stories and from contested points of view, I have attempted to jeopardize the status of the event, to displace the received or authorized account, and to imagine what might have happened or might have been said or might have been done. By throwing into crisis “what happened when” and by exploiting the “transparency of sources” as fictions of history, I wanted to make visible the production of disposable lives (in the Atlantic slave trade and, as well, in the discipline of history), to describe “the resistance of the object,” if only by first imagining it, and to listen for the mutters and oaths and cries of the commodity. By flattening the levels of narrative discourse and confusing narrator and speakers, I hoped to illuminate the contested character of history, narrative, event, and fact, to topple the hierarchy of discourse, and to engulf authorized speech in the clash of voices. The outcome of this method is a “recombinant narrative,” which “loops the strands” of incommensurate accounts and which weaves present, past, and future in retelling the girl’s story and in narrating the time of slavery as our present.” (emphasis mine)

For those of us who are intimidated by the boundlessness of dreams, as I often am, Michel de Certeau4 also offers two ways to untether individuals from the modes of thought which have destroyed them and, in turn, to make space for life:

Attend to and recruit the past for the sake of the living. Establish who we are in relation to who we have been.

Interrogate the production of our knowledge about the past.

I want to return briefly to the shape of the archive I introduced in the beginning—the body, our flesh bodies in particular.

We’re told that our bodies contain memory, that they remember even when we don’t, that they “keep the score”. Our bodies are our direct encounter with the world. When I talk about a brush with racism, or sexism, or any adjacent structure of oppression, I mean that my skin has been under the bristles of violence. I mean that it has touched me. There are feelings and experiences (physical or otherwise) that have made a home of my body. Hands are our first receivers—of food, support, the faces of people we love. They are also our first givers, and protectors. Hands tell stories—puppetry, signing, cooking. They soothe, heal, create warmth.

So while it is true that some stories die with us, I also believe some can be passed down somatically. Research has shown that South Asians today have a greater tendency to store fat instead of burning it because over generations, our bodies have adapted to starvation, having had to survive at least 31 famines. Hindus and Buddhists believe in reincarnation: the rebirth of a deceased person’s soul in another body. So, if to exist in a body is to be, and to be is also to do, I think we are doing being well.

Hartman, S. (2008). Venus in Two Acts. Small Axe 12(2), 1-14. Duke University Press.

Foucault, M. (2003). Lives of Infamous Men. In P. Rabinow and N. Rose (Eds.), The Essential Foucault, 284. New York: New Press.

Incidentally, the MoMA ran (and is maybe still running) an exhibition by the same name. See here for a piece I wrote about the museum as an archive (!) of violence and neoliberal architecture, amongst other things.

de Certeau, M. (1992) The Writing of History. New York: Columbia University Press.

this was incredibly comforting to read, even as the terrains you've identified -- of colonial violence, of bodies, of stories, of dreaming -- are in themselves often cavernous, discordant, aching. i experienced here a promising glimmer of light. hoping you are well 💖